As far as the mortgage market goes, it seems like things couldn’t get much worse than they were in 2018.

There was the banking royal commission, which absolutely obliterated the banks over their irresponsible lending practices.

There was the credit slowdown led by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, which forced lenders to limit the number of investors and interest-only loans on their books.

And there were a number of out-of-cycle interest rate rises, which saw investors paying up to 20% more for their loans than owner-occupiers.

All of the above conspired to make it difficult for even the most vanilla, high-quality borrowers – those with low debt and good serviceability – to secure finance as the banks severely tightened their criteria.

Not only that, but loan applications are “taking weeks longer than before to get processed”, says Philippe Brach, founder and CEO of Multifocus Properties & Finance.

“Assessors keep coming back with more questions every time you answer the previous ones, and frankly a lot of them are pedantic and unnecessary. It is almost like they are looking at reasons for not giving you a loan,” he says.

So where does that leave borrowers today? Is it going to be just as difficult to get a loan in 2019 – or are the financial tides set to turn?

How did we get here?

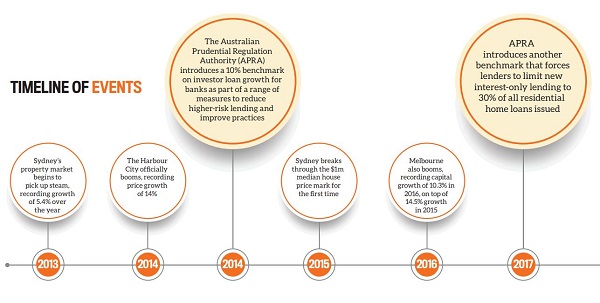

It all began way back in 2014, when the property market began heating up to the point where regulators, leaders, policy creators and decision-makers started to get nervous.

The property markets in Sydney and Melbourne were booming; values began increasing in the double digits every year, and borrowing was at an all-time high. This made people nervous, particularly about the risk that borrowers and property buyers could overextend themselves financially.

So in 2014 the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) stepped in, introducing a 10% benchmark on investor loan growth as a temporary measure, in an effort to reduce higher-risk lending and improve practices.

In March 2017, APRA followed this up by forcing lenders to limit new interest-only lending to 30% of residential home loans issued.

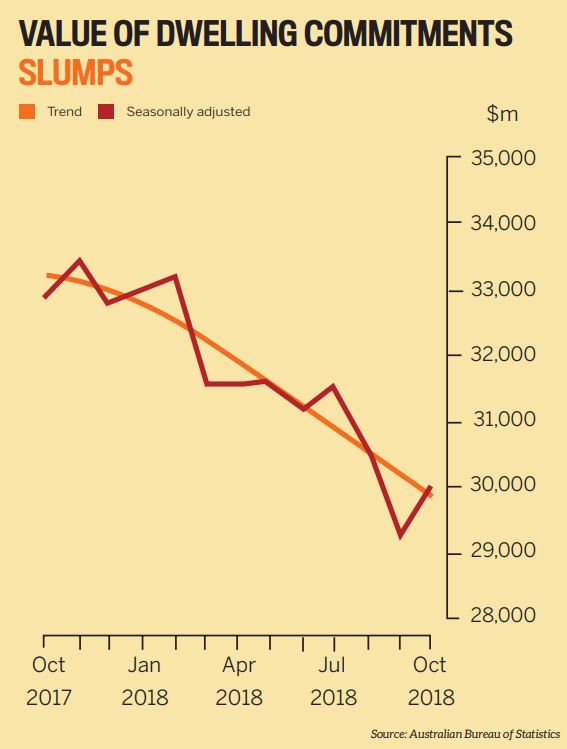

These measures worked; they had a noticeable impact on investor lending as banks started to lift investor interest rates and require bigger deposits. Investors took a massive hit as their ability to acquire property was diminished. In fact, following these measures, new interest-only loans fell well below the cap of 30% to just 16% of new loans issued (at their peak, 46% of loans were interest-only).

Then the royal commission into banking and financial services came along. It highlighted a number of irresponsible practices by the banks, which made lenders even more cautious when approving loans.

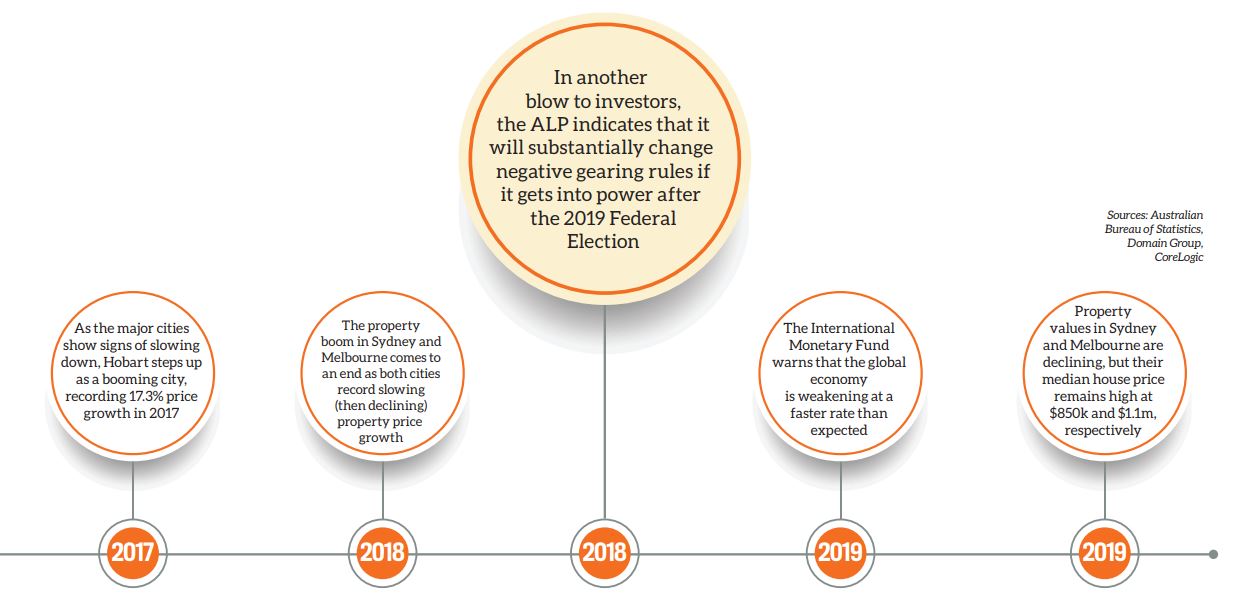

Combined, the above measures worked to limit investors’ ability to buy. They also helped to take the heat out of the property market, which slowed property price growth in Sydney and Melbourne. It worked so well that price growth didn’t just slow, it came to a complete halt – and then started falling.

As a result, APRA chairman Wayne Byres confirmed that the limits and measures the regulator imposed would be removed, as they had “served their purpose”.

“The benchmark on interest-only lending was put in place as a temporary measure in 2017, with the aim of reducing the level of interest-only lending and improving the quality of mortgage portfolios,” he said.

“Since the introduction of the benchmark, the proportion of new interest-only lending has halved, and interest-only lending at high loan-to-valuation ratios has also declined markedly.”

Investor demand waned throughout 2018 amid higher interest rates, tightening loan criteria and slowing growth. So, in 2019, where will things go from here?

And if you do want to add to your portfolio this year, are you likely to have a tough time getting finance?

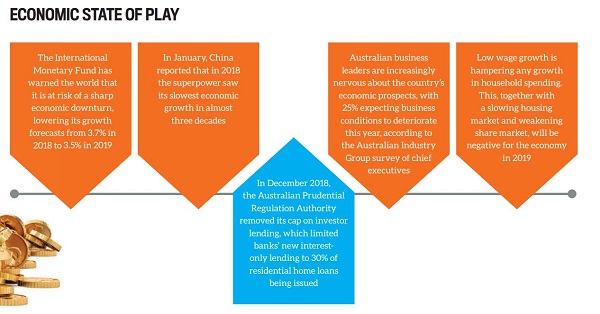

The report warned of a number of triggers – including Brexit, the US-China trade war, and China’s economic slowdown – that could lead to even lower property price growth.

“A range of triggers beyond escalating trade tensions could spark a further deterioration in risk sentiment with adverse growth implications, especially given high levels of public and private debt,” said Gita Gopinath, IMF chief economist.

“The downward revisions are modest, however we believe the risks to more significant downward corrections are rising.”

Add the Australian Labor Party’s potential changes to negative gearing into the mix and it’s easy to see why investors are cautious about taking any action right now.

But for those still keen to buy, let’s look at their finance prospects for the year ahead:-

- Getting loan approval in 2019

- Are non-banks the answer for investors?

- 'Responsible lending' in the spotlight