Australia's rental market will only get tighter throughout this year.

Australia’s rental crisis will worsen as vacancy rates remain remarkably low, the rental stock looks slim and rents continue to skyrocket.

So how did we get into this rental crisis?

What does it mean for property investors?

And how can we overcome it?

First, let's take a deeper dive into the data

According to the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data, there were nearly 9.8 million households in Australia in 2021.

And the majority are owner-occupiers.

In fact, 66-67% of those households (or 6.2 million households) are homeowners, according to data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Note: 2.9 million Australian households are mortgage-free and the remaining 3.3 million are homeowners with a mortgage.

Meanwhile, 31% of these 9.8 million Australian households (which equated to around 7 million people) are renters.

- 91% of tenants( 2.4 million households) rent from private landlords,

- 3% of our population, or 277,500 households, rent from state or territory housing authorities and

- 2.4% of our population, or 223,600 households, rent from other landlords.

The remaining 2.1% (192,200 households) are other tenures, including households that are not an owner with or without a mortgage, or a renter.

Homeownership breakdown also differs by state

Across the states and territories, the homeownership rate is highest in Western Australia (69.3%) taking over from Tasmania (72%) in 2017-18, and lowest in the Northern Territory (59%), which may relate to the average housing costs in those respective regions.

Here’s the homeownership breakdown in each Aussie state:

- New South Wales: 64% homeowners, 33% renters

- Victoria: 68% homeowners, 29% renters

- Queensland: 64% homeowners, 35% renters

- Western Australia: 69.3% homeowners, 28% renters

- South Australia: 69% homeowners, 30% renters

- Tasmania: 68% homeowners, 29% renters

- Northern Territory: 59% homeowners, 40% renters

- Australian Capital Territory: 69% homeowners, 28% renters

Even age plays a significant role

It probably comes as no surprise that homeownership increases with age.

Data shows that up until their mid-30s, the majority of Australians rent rather than own a home, likely because it takes time to save a house deposit, and also these age groups have yet to settle down.

The data suddenly turns in the 35 to 44 age bracket with more people settling into home ownership – swapping roommates for spouses and creating new families.

The proportion of homeowners and renters by age of household reference person:

- 15 to 24: 10.4% homeowners, 83.5% renters

- 25 to 34: 40.7% homeowners, 55.7% renters

- 35 to 44: 56.7% homeowners, 41.5% renters

- 45 to 54: 72.0% homeowners, 26.3% renters

- 55 to 64: 79.1% homeowners, 19.1% renters

- 65 to 74: 81.7% homeowners, 16.0% renters

- 75 and over: 83.0% homeowners, 12.9% renters

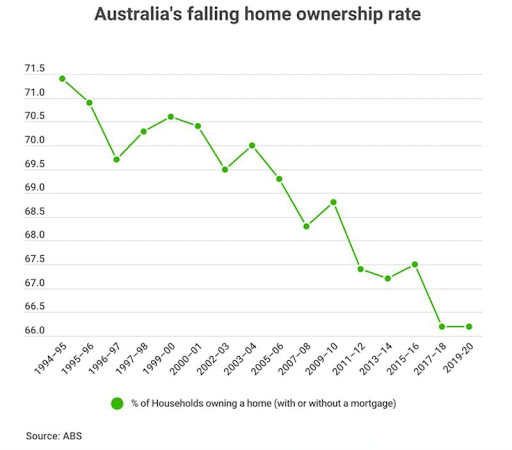

Homeownership rates are falling

The rate of homeownership in Australia has been declining in recent years.

According to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the homeownership rate fell from 71.4% in 1991 to 67.8% in 2021.

There are several factors that have contributed to this decline.

One of the main factors is the increasing cost of housing, which has made it more difficult for many people to afford to buy a home, especially in our two big capitals cities Sydney and Melbourne.

Another factor is the changing demographic and preference of younger generations to lay their roots down later in life and initially rent rather than buy a home.

At the same time the rate of decline amongst low-income households has fallen dramatically.

Government data shows that certain age groups exhibit more significant declines in homeownership rates over time.

For example, between 1971 and 2016, the number of homeowners aged 25-34 years dropped to 44.6%, from 57.0%, and in the 35–44 year age range, rates fell to 62.2%, from 71.4%.

And the numbers have dropped further to today’s figures of 40.7% for ages 25-34 and 56.7% for ages 35-44 respectively.

In fact, homeownership rates for younger households peaked in 1981, at 61.1% for those aged 25–34 years and 75.3% for those aged 35–44 years.

The data also shows a decline in income.

Lower-income households have experienced greater declines in levels of home ownership than more affluent households.

The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) found that the steepest decline in home purchase rates for the 25–34, 35–44 and 45–54 age groups were in the bottom two income quintiles between 1981 and 2011.

Meanwhile, Parliament data also shows that between 1998–99 and 2013–14, rates of home ownership fell across all after-tax, equivalised income quintiles (that is, adjusted for size and composition), except for the highest quintile where the rate of home ownership increased slightly.

This is interesting data, but what about the renters?

Of the estimated 9.8 million households, 31% are renters.

Now that’s a huge volume of renters needing or looking for a rental property.

And, unlike many other countries, the majority of Australian renters do so from private landlords (26%) with only around 3% renting via state or territory housing authorities.

Of course, if the number of homeowners is declining among younger Australians and lower income brackets (which makes sense given our high property prices versus many other countries) it makes sense that there is a bottleneck of renters unable to leap onto the property ladder and become owners.

Not all tenants are the same

It’s worth remembering though that while a small group of Australians will always be socially disenfranchised and in need of social housing, many are forced to rent because they can’t afford to buy a house… there are also a large group of renters who rent a property out of choice.

Some may have recently moved to a new state, others to a new location because of their job.

Others may have just got married (or divorced) and then there are those who are renovating their home, buying a home or who have decided to use rentvesting strategy (rent where they want to live but can't afford to and invest where they can afford to buy property).

The problem with Australia’s rental market

Of course, the rental crisis hasn't just happened overnight and is the result of a perfect storm of events unlikely to be reversed anytime soon.

The government has relied on private landlords to provide rental accommodation, but over the last few years, various elements including state governments have created an unpleasant ‘us versus them’ culture between landlords and tenants.

They have introduced significant residential tenancy legislative changes favouring tenants and alienating landlords as governments try to use private investors as a means to prop up government budgets suffering from bulging debts.

After all, most landlords are ordinary Australian mums and dads who only own one or two properties, and who are trying to secure their financial futures.

These property investors take on a commercial risk and expect to receive adequate rewards.

Other factors leading to the rental crisis include:

- APRA implemented restrictive lending policies commencing in 2016, which significantly reduced the number of investors

- Higher bank interest costs for investors over owner occupiers

- Diluted depreciation allowances for property investors adding pressure to investment cash flows

- State government rental legislation favouring tenants at the expense of landlords

- The recent reduction in new apartment construction which would normally boost supply

Our rental markets can’t cope

Currently, 91% of Australia’s 3.2 million rental properties are funded by everyday Aussie investors.

Over the last 30 years despite Australia's population increasing by 8.4 million people, state governments have sold off more than 100,000 publicly owned rental properties.

While there are about 3.3 million properties around Australia that can be used for rental purposes, currently only around 1% of these are advertised for rent.

In fact, currently, there are just over 33,000 properties advertised for rent, about half the number they were a year ago.

Over the last decade just over 1,000,000 first-home buyers have moved out of the rental market and now own their own homes, often helped by government incentives, but with overseas migration ramping up, and overseas students returning to Australia, supply is too limited and our rental markets just won't cope.

Where are all the overseas migrants going to live? They don't bring her home with them.

Not only that, but recent surveys have shown that up to a third of investors have either sold up or are planning to sell up their investment properties, in part because they feel they are losing control of their financial assets.

The issue of short rental property supply is concerning, and it is getting worse by the day.

Vacancy rates are also an issue

The tightness in supply is also evident in the national rental vacancy rate, which is at record lows

Interestingly, the data also shows that Australia’s tight rental market appears to be shifting back to major cities, suggesting that many who fled to regional Australia during the pandemic have begun to migrate back to the cities, along with a sharp uplift in international migration.

This is especially the case in Sydney and Melbourne where supply has tightened significantly.

Australia’s most major capital cities have seen the biggest drops in rental supply over the past year, with declines of 32.8% in Melbourne, 24.2% in Sydney, and 22.7% in Brisbane, PropTrack’s rental report shows.

Meanwhile, the largest uptick in rental supply over the year was recorded in Canberra (30.2%), regional Tasmania (14.4%), and regional New South Wales (11.1%).

Affordability crisis also hits

Not only is there a huge issue with rental property supply, but this is also creating an affordability crisis.

The 2020-21 property boom saw many investors offload their properties to take advantage of booming prices, but now, with fewer investors owning and buying homes, the tight supply of rental properties combined with strong demand is continuing to put pressure on prices.

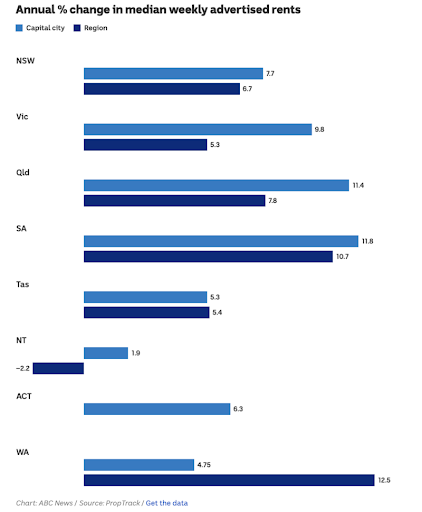

PropTrack’s latest rental report shows that median weekly combined rents increased 4.3% over the September quarter - which is the fastest quarterly pace of growth on record.

Year-on-year rental prices have increased by 10.3%, which is the strongest growth witnessed in seven years.

Rental price changes also reflect an uptick in demand for city locations.

Capital city house rents rose 4% over the quarter and unit rents were 2.2% higher while in regional areas, house rents increased 2.2% over the quarter, while unit rents were unchanged.

These price increases are hitting tenants hard at a time when the cost of living is also surging, with many priced out of large areas of the rental market.

Tackling the rental crisis

Our governments are now, very belatedly, starting to address the rental crisis.

The latest budget outlined a National Housing Accord, which is an agreement signed between governments, investors, and the construction sector, aimed at addressing the supply and affordability of housing.

Which would in turn ease pressure in the rental market.

There are several direct impacts of the housing accord which are worth noting.

One million new homes is an ambitious target when considering the economic context, and will keep construction activity elevated.

The budget references a target within the accord to build one million new homes from 2024 over five years, with the bulk of this coming from the private sector.

One of the main critiques of a target for one million new homes in a five-year period is the target is not ambitious, given recent completions match this anyway.

ABS dwelling completions data suggests 974,732 homes were constructed in the five years to June 2022, and an average of 1,010,723 have been completed on a five-year basis since 2017.

Under the housing accord, 10,000 affordable homes will be supported by the Federal Government over five years, 10,000 from state and territory governments, as well as 30,000 new social and affordable homes, which were announced in the lead-up to the May federal election.

This will free up land for superannuation funds and large corporations to provide large apartment and house builds specifically for tenants.

While there is reference throughout the budget of incentives for the private sector to deliver affordable housing, there will be some finer detail required about how this can be incentivised and enforced.

It’s also unlikely they will be prepared to accept the low returns or type of treatment that private investors have had to endure.

The problem with current policies

Current policies are not supportive of attracting more private property investors to supply rental accommodation.

Sure the government is looking for large corporations to get into the ‘build to rent’ segment, but this will take time and only occur in certain locations.

Also, given the government recently increased the overseas migration threshold to 195,000 people a year to attract skilled labour and an uptick in international students, this will create an extra demand for 75,000-80,000 properties a year.

Australia is reportedly receiving 10,000 applications per week for international students, which our economy needs are the education sector in one of our largest export industries and provides significant economic benefits to Australia broadly.

But where are all these people going to live?

The new government policies won’t even tackle half the issue.

What we really need to tackle this crisis

The share of lending to investors is trending lower and while there is some supply coming via build-to-rent, this will be outweighed by the demand uptick resulting from the re-opening of our international borders and the decline in first-home buyer activity.

I believe the government needs to encourage private investors to get back into the market in order to provide the rental accommodation the government and large corporations cannot.

I can't see any other way that this rental crisis will end.

After all, it's a supply issue.

And we’re currently dealing with a significant rental shortfall and long lead times with built-to-rent accommodation.

More investors would translate to more rental stock, which would ease demand levels in the rental market and help to overcome an overheating of rental prices.

It seems an obvious solution to me, and one which could help to cool the market quickly.

Not only will it help to improve the rental market if this happens, but it will also be the makings of another property boom.

The rental crisis creates a window of opportunity for property investors

Currently, I see a window of opportunity for property investors with a long-term focus.

This window of opportunity is not because properties are cheap, however, when you look back into three years' time the price you would pay for the property today will definitely look cheap.

The opportunity arises because currently consumer confidence is low and many prospective homebuyers and investors are sitting on the sidelines.

Note: 2023 will be the year our property markets reset and the beginning of a new property cycle.

Sooner rather than later many prospective buyers will realise that interest rates are near their peak, and inflation will have peaked as the RBA's efforts have brought it under control.

And at that time pent-up demand will be released as greed (FOMO) overtakes fear (FOBE - Fear of buying early), as it always does as the property cycle moves on.

We saw an opportunity like this in late 2018 - early 2019 when fear of the upcoming Federal election stopped buyers from entering the market.

And look at what's happened to property prices since then.

I saw similar opportunities at the end of the Global Financial Crisis and in 2002 after the tech wreck.

History has a way of repeating itself.

Strategic investors will take advantage of the opportunities our property markets will offer over the next couple of years maximising their upsides while protecting their downsides.

Now I'm not suggesting taking advantage of tenants, what I'm suggesting is to recognise there is currently a problem (lack of rental accommodation) and provide a solution.

But don't try and time the market - this is just too difficult.

And don't look for a bargain - A-grade homes and investment-grade properties are in short supply and still selling for reasonably good prices.

These high-quality properties will tend to hold their value far better than B and C-grade properties located in inferior positions and inferior suburbs.

While it may feel strange and counterintuitive to buy in a correcting market, there are many valid reasons why this is the BEST time to buy….and history has told this story over and over again.

- There is less competition.

- You have more time to research and select the right property

- You have time to complete due diligence checks.

- Consumer sentiment is low – this is the ideal time to take advantage of the situation during negotiations and lock in a good price.

- Once migration really ramps up, this will worsen the rental crisis.

- There is no risk of oversupply – with construction costs rising so rapidly, the volume of building approvals has trended down substantially. This will mean we are now entering the next cycle of constant undersupply in the property market which will support prices.