As Australia continues to grapple with the challenges of skyrocketing residential rents, the question of whether rent controls could be a viable solution has arisen.

Some proponents of rent controls point to the United States as an example, where cities like New York and San Francisco have implemented such measures.

However, when we examine the effects of rent controls in these cities, it becomes clear that this approach is far from a panacea.

In fact, rent controls may be aggravating the problem rather than alleviating it.

First, let’s start with the state of play

We currently have a national rental vacancy rate of 1.1 per cent, where closer to 2.5 – to 3% is a ‘healthy market’.

In other words, there are not enough homes to rent in Australia, and now the cost of renting is rising rapidly after a decade of slow rental growth.

While around 30% of Australian households rent, the supply of properties is severely constricted and worsening.

Available rental properties dropped almost 15% over the past year, and more than 33% in the past five years, with around a quarter of the properties currently for sale previously being rental properties.

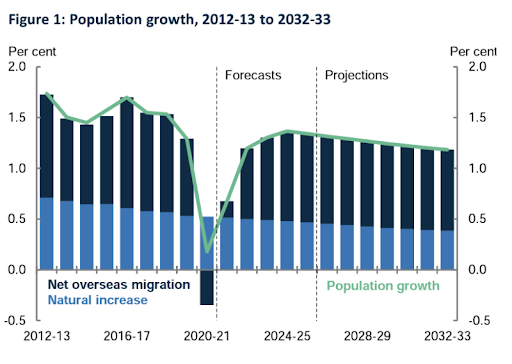

And with most of these being sold to home buyers there is no end in sight to the dire rental situation as we're just not building enough new accommodation to cope with the increased demand now that there's been the resumption of immigration and the return of foreign students.

There is nothing new about this, governments have been warned that across our four largest capital cities in 2024 will be less than a quarter of the 2018 levels.

And the recent Budget suggested our population could increase by one and a half million people in the next three years if you take all the eduction migrants and temporary visa holders into account.

To put that statistic into context, it is the equivalent of adding five Canberra’s worth of people to Australia’s current population in only 3 years, but without the necessary housing and infrastructure.

In other words, it is the equivalent of adding another Perth to Australia’s population in just 4-4 years.

At the same time, the majority of rental accommodation is provided by the private rental market - ordinary Australian mums and dads trying to secure their financial future - but rising mortgage costs, increased government interference and support of tenants, and higher compliance costs mean more and more of these investors are selling up or putting their properties on Airbnb only exacerbating the rental crisis.

But it's more than immigration it is causing the housing crisis

Sure, skyrocketing immigration numbers will worsen our housing crisis, but there’s more to it than that.

The severe shortage of accommodation can be attributed to several key factors, including increased demand for space during the COVID-19 pandemic, a decline in average household size, and the resulting surge in demand for homes.

It’s well-recognised that the COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant shift in people's preferences for living spaces.

As people started spending more time at home due to lockdowns and remote work, there was an increased desire for larger, more comfortable living spaces.

This sudden demand for extra homes contributed to the housing crisis.

But Australia's average household size was already decreasing prior to the pandemic.

The Reserve Bank of Australia found that a one percentage point decline in average household size created 120,000 new households, all of which needed homes.

This increased demand for housing put significant pressure on the market.

So why consider rent controls?

Recently the Greens proposed rent capping which would regulate (ok – cap) the amount by which landlords can increase rent on their properties.

While this might seem like a benevolent measure to protect tenants from exorbitant rent increases, the reality is far more complex.

Beware of unintended consequences:

Note: Rent controls can lead to a decline in housing quality.

One of the unintended consequences of rent controls is that they can lead to a decline in the quality of available rental housing.

When landlords are unable to charge market rates for their properties, they may become less inclined to invest in maintenance and improvements.

This can result in a deterioration of the housing stock, leaving renters with fewer quality options.

Note: Rent controls may reduce the supply of rental housing.

By limiting the potential returns on investment for property owners, rent controls can discourage new development and reduce the overall supply of rental housing.

This, in turn, can exacerbate the issue of housing affordability, as the limited supply of available properties drives up rents even further.

Note: Rent controls can create unfair distribution.

Rent controls often benefit those who are already in controlled properties, while leaving those who are searching for a new rental to face the full brunt of the market.

This uneven distribution of benefits can lead to a two-tiered rental market, where some renters enjoy artificially low rents while others face skyrocketing costs.

Note: Rent controls can stifle mobility.

When tenants are locked into rent-controlled properties, they may be less inclined to move, even if their circumstances change.

This can lead to a lack of mobility in the rental market, making it difficult for those searching for a new rental to find suitable housing.

Is Build to Rent the answer?

The recent Federal Budget announced tax incentives to promote institutions investing in the nascent Build to Rent (BTR) sector.

It’s possible we could see up to 150,000 new BTR apartments delivered over the next decade, about two-thirds of which will likely be in Melbourne.

Build-to-rent apartment projects are designed and built by a developer who retains ownership of the building when it is complete, and the units must offer a guaranteed lease period of at least three years for those seeking the security of tenure.

The BTR concept is relatively new to the Australian housing scene and the largest institutional developer of them in Australia, Mirvac, has only two completed BTR buildings current experience suggests that rents in these complexes will be around 25 per cent more expensive than what's currently available on the open market.

So this initiative is not going to deliver large-scale affordable accommodation in the short term.

What’s the answer to the rental crisis?

The simplest answer is to encourage more ‘Mum and Dad’ investors back into the market.

This investor pool supplies more than 65% of rental properties in Australia and cannot be ignored, yet they are leaving the market in droves.

Rising mortgage costs, higher Land Tax and insurance premiums, and State legislation that reduce the ability of landlords to control their investment effectively have dramatically increased the risks for property investors, and many have voted with their feet.

Yet it would not take much in the way of tax incentives and the removal of discriminatory mortgage pricing to encourage investors back into the market to provide the type of rental accommodation that is desperately needed.

The problem is that this is politically unpopular given that investors and first-home buyers tend to concentrate on similar sorts of properties.

The government should also consider a longer-term option of diversifying who provides rental accommodation in Australia, not solely depending on private investors who currently supply almost all of the rental accommodation.

Firstly, the government should be providing more rental housing, particularly focusing on providing affordable housing to vulnerable groups.

Then the Build To Rent incentives should boost supply, but this will take some time.

Another solution is to incentivize offshore buyers back into the market.

In the past foreign investors bought a significant portion of the new apartment complexes built in our capital cities, however a range of additional taxes and charges over the last decade pulled the welcome mat out from under them and discouraged them from buying Australian property.

Since foreign investors are restricted from buying new properties, this would also ensure more construction takes place further increasing the housing supply, but in the past, they underpinned the presales that allowed new apartment complexes to be developed.

While we don't recommend buying into the types of apartment towers dominated by foreign investors, we do appreciate them being built to alleviate the housing shortage.

In conclusion, we’re in the middle of a rental crisis and while there are no easy answers and no end in sight, rental controls are not the answer to Australia's rising residential rents.

Instead, a multifaceted approach that addresses both supply and demand-side factors is required to ensure that all Australians can access safe, secure, and affordable housing.