In modern property markets, development projects carry more than a modicum of risk. “Warren Buffett has been quoted as saying that the goal of all investors should be to achieve the maximum return for the minimum risk,” explains Matthew Lewison, founder and CEO of Open Corporation Diversified Property Group.

“Property development is an inherently risky business, and that is partially why there are premium returns to be made from developing.”

While it is possible to generate sizeable profits from multi-dwelling developments – indeed, Lewison’s business specialises in creating highyielding property development funds for small to medium-sized investors – you need to be well aware of the various risks involved.

One such risk is finance, which for Lewison has often actually become an opportunity.

“Development finance is a tricky business that ‘buy and hold’ investors often mess up, because they’re used to gearing their purchase to take advantage of leverage. Leverage can be your friend in development too, but generally only when you have eliminated the planning and sales risk of a project,” he says.

“I have purchased some of my most profitable projects from recreational developers who bit off more than they could chew, settling on the land purchase with 60% gearing and then scraping enough cash together to get a permit. When they went to the bank to get funding for construction – after signing up a few dozen sales contracts, I might add – they got laughed out of the building and had to put their property on the market for a quick sale, as their lender said they didn’t have the means to fund construction.”

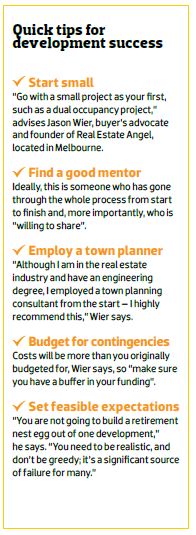

This is just one of the traps you can fall into when attempting a larger-scale development project, which is why most experts advise investors not to dive in without some sort of experience or track record behind them.

“Unfortunately, too many people get caught up chasing the high profits and jump into a development without fully understanding what is involved,” Lewison adds.

If that’s the case, then what do you need to know before attempting this type of sophisticated, multi-dwelling development project? We asked the experts to weigh in.

#1 Renovating is a developer’s ‘rite of passage’

Several years ago, Peter Koulizos built a group of six dwellings in Port Noarlunga, South Australia.

“I held on to them and they’re great investments. They’re positively geared and I made a good profit out of the development project itself,” says Koulizos, an experienced investor, property lecturer and author.

“That said, it is the riskiest of all property investing strategies. It can be rewarding, but I wouldn’t encourage anyone to go from zero to property developer until they’ve at least tackled a renovation.”

Renovation, Koulizos says, is a property investing ‘rite of passage’.

“You get to mix with tradies, learn their lingo, and work out what some things cost on a per square metre whether it’s tiles or carpets, or concrete or pavers,” he explains.

He believes it’s an essential learning curve every investor should experience before diving into a development, especially a multi-dwelling project, as you learn how to cope with small setbacks in situations where you don’t have as much to lose.

“If you encounter rainy weather during a renovation or development, your project may be out of work for three weeks, but the bank still wants mortgage interest for that period,” Koulizos says.

The interest payable on a singledwelling mortgage will be easier to manage than on a multi-dwelling development, which could see you exposed with “a million-dollar [loan] outstanding… and nothing to generate a profit or sell until the end,” says Koulizos.

Takeaway

You don’t know what you don’t know, and some lessons are better learnt on a small-budget project rather than a multimillion-dollar development. “Whatever your project is, make sure you start at the finish first,” Koulizos adds. “Work out what you can sell the finished product for, then work out your feasibility from there.”

#2 The role of a town planner is largely misunderstood – but essential

The training, skills and role of a consulting town planner in a development project is often underestimated and “generally misunderstood” by new or aspiring development proponents, but they play an essential role in ensuring a smooth project, says Graham Clegg, principal of G W Clegg & Company, Planning and Environment Consultants in Brisbane.

“I recently turned 50 and I reckon my father still wouldn’t be able to tell you what I do for a living if you asked him,” he jokes.

“By the very nature of their training, a town planner working in the development industry has multidisciplinary knowledge, because their university course touches on a broad range of subjects including engineering, environmental science, valuation, urban design, property economics, architecture, to name but a few.”

While a town planner is a specialist in the area of planning legislation and policy, along with local and state government approval procedures, they are also able to identify the specialist needs of a development project. Clegg says this can be “invaluable” when it comes to properly scoping a project and budgeting financial and time resources.

“A competent development application submission to council will expedite council processing timeframes and allow the project to start quickly, reducing holding costs,” he adds.

“We’ve had a number of clients come to us who thought they could proceed on their own without a town planner, only to find they’ve been caught up in the DA stage unable to satisfy council requests and requisitions. [Engage a town planner] at the front end of a project to save both time and money.”

Takeaway

Market knowledge, budget advice and project-specific expertise from a town planning professional won’t just save you time; it can ultimately save you money, too. “Risks are inherent in all development projects, but ‘educated risk’ is key to being prepared for managing issues,” Clegg says.

#3 You may be able to make more money elsewhere in property

As a hands-on strategy that demands a lot of time and energy, developing isn’t suitable for everyone. But many investors tackle such a project because they like the idea of becoming developers, and become attached to the concept of the big dollars they think they can make.

In reality, the realistic profit margin when tackling a multi-dwelling development can be modest, with multiple opportunities for your profits being eaten away when unexpected issues arise. Indeed, this is a lesson that Paul Wilson, founder of We Find Houses, says many investors don’t learn until they’re midway through their project.

“You really need to make sure that you don’t buy into a project based on emotions,” Wilson says. “Some investors get all excited about being able to get their teeth into a development, only to find in the end that they were just ‘busy being busy’, and they actually didn’t achieve a financial outcome that justified the amount of time and money they dedicated to the project.”

Wilson has a client who is currently constructing a triplex on a block of land, after setting themselves a goal of generating a 15% return.

“There’s a good chance they might not reach their goal; in fact, they’ll probably make about a 10% gain,” Wilson says.

“The resulting properties are going to be very financially efficient, in that they’re going to return 6% rents with full depreciation, and the project will generate a clear $100,000 in capital growth. They’re happy with that result, but for some, $100k isn’t enough [profit] to justify the time and energy of doing the project.”

Takeaway

If you’re already overscheduled with a busy day-to-day life, a development project may add maximum stress for minimum return. “Be very clear on your goals – if you’re going to hold the properties on completion, it often works out better,” Wilson says.

#4 GST could haunt your development profits

When reviewing a potential development project, many everyday investors forget to factor in the crucial and potentially profit-crunching financial aspect of GST, warns Koulizos.

“If you have a house at the front of the block and you’re building a duplex pair at the back of the site, then you’re creating something new – and when you create something new, GST is applicable. So you would have to pay GST on the sale of the duplex pair at the back,” he explains. “It can really eat through your profits, and unfortunately I’ve seen this happen

[to developers] at the end, when it’s all too late. Investors don’t make as much as they project because they underestimate the costs and overestimate the profits, then they really end up in the red if they sell and then have to pay GST.”

You can minimise your GST obligations by registering for the Margin Scheme, which allows you to pay GST on the margin between the cost of the land and the property sale price.

“If you calculate that the land component of the property cost you $250,000 and you sold it on completion for $550,000, then you would only pay GST on the difference of $300,000, rather than on the full amount,” Koulizos explains.

“And if you’re registered for GST, you can also claim for the GST you’ve paid on the build.”

Another way to avoid this cost is to hold the duplex pair indefinitely, Koulizos says. “Remember, you only pay that GST if you sell,” he says.

Takeaway

Meet with an accountant experienced in property developing before you begin your project. “If you mention the Margin Scheme and your accountant looks at you blankly, then find another accountant,” Koulizos advises.

#5 ‘Contract conditioning’ is key to a successful development

To be a successful property developer cultivating a multi-property site, you need to first understand the risks involved so you can work on eliminating them – or at the very least, minimising them.

One of the easiest and most efficient ways to achieve this is by conditioning the contract of purchase, explains Lewison, as this allows you to minimise your risks at the outset.

“The ideal project is one that offers a premium return, but that has risks that you know, understand and can either eliminate or manage,” he says.

“You don’t want go unconditional [on your contract] until the risks are eliminated, so you could for instance add a ‘subject to planning permit’ clause. We also usually get a builder’s price estimate before we go unconditional on any offer.”

Lewison admits to negotiating with subcontractors and entering into tentative side agreements while still in due diligence, to ensure he has the resources (and the right project budget in mind) if the deal proceeds.

Takeaway

Use your due diligence period to minimise project risks. “We are more than happy to have a crack at solving problems while the site is still in the hands, and at the risk, of the vendor,” says Lewison. “Think of it like testing the depth of the water with a probe before you jump in head first.”

Profit-crunching lessons on a 5-townhouse project

At just 21, Michael Tiemens began investing in real estate after his mum invited him to attend a few seminars about creating profits through purchasing property.

“I’d been working full-time for about four years. I had saved up some money and was ready to get started,” Michael, now 26, recalls.

But it wasn’t a standard rental home he decided to embark on as his first foray into real estate; it was a project far more ambitious.

“For my first property, I relocated a one-bedroom granny flat to a holiday park. I got my hands on a new piece of dirt in Bonny Doon, and because it was a holiday park I didn’t buy the land – in these situations, you lease it for a small fee, renewed every 12 months,” Michael explains.

He spent $3,000 preparing the land to receive the home, and another $8,500 transporting it, before commencing $40,000 worth of renovations, including a new roof, an outdoor area with a deck, and refreshed fixtures and fittings inside.

“I sold it for $85,000, so I made about $35,000 profit,” Michael says.

“It was a good learning curve and a great first experience.”

It certainly qualifies as an unusual induction into the property game, but it also begs the question, where did the granny flat come from?

This leads to Michael’s second real estate project – a development consisting of five townhouses in Croydon, around 27km east of Melbourne, Victoria.

“I pulled the granny flat from a property in Croydon that my mum and I purchased together for $560,000, with the intention to develop units on it,” Michael says.

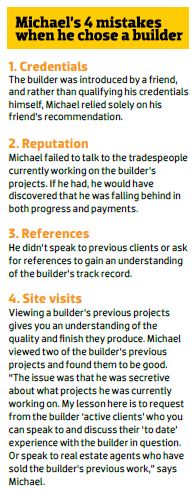

“We had a builder that went really south on us at the start of construction. We had requested several quotes and narrowed it down to two builders – and I ended up choosing the wrong guy.”

The builder was introduced by a friend, and Michael admits he was “a little naive and fresh”, and made some mistakes in qualifying him.

“I didn’t go on-site and talk to the tradespeople working on his projects. I did contact the builders’ practitioners board to see if he had any faults against his licence, and that came up clean, but I didn’t do the homework on the ground and speak to people he’d worked with,” Michael says. “If I had done that, I would have discovered he was suffering some major cash flow issues.

He was behind on a lot of projects he’d committed to – to the point where on some projects he’d completely stopped work – and he wasn’t paying some of his tradies, either.”

Consequently, six months after signing the contract and paying a $50,000 deposit, Michael’s project was on struggle street.

The builder hadn’t shown up on-site once, despite Michael issuing breach notices and legal letters compelling him to fulfil his contract.

Another two months later – eight months after commencing – the builder had only completed the site cut and built a retaining wall. But despite being so far behind, he refused to let Michael out of his contract.

“My solicitors weren’t working hard enough, so I gave them the flick and found a guy who was a real gun. He ended up getting us out of the contract after two-and-a-half months, but I still had to pay the builder $100,000 in total – plus I had a legal bill of close to $50,000,” Michael says.

“It’s the biggest lesson I’ve learnt in this business so far. I’ve got to really qualify people. That builder went bankrupt not long after, and I believe he may have lost his licence as well.”

The week after ending the contract, Michael engaged the other builder he had shortlisted – “The builder I should have gone with from the start!” – who immediately got to work.

“He went over and above to get the townhouses completed in just 10 weeks. We’d lost all of our presales due to the delays, so I got some great salespeople on board and we got all five townhouses sold within the space of building them,” Michael says.

“Initially, we were set to generate around $250,000 to $300,000 in profits. We broke even in the end, as the interest repayments really hurt, and after losing presales, commissions and legal fees there wasn’t a lot leftover.”

“It was a crazy period of time; you really do learn a lot about yourself when you’re pushed to the limits. But I’m moving forwards and I’ve got a few different joint venture partners who I’ve been working with; together we’ve got three projects on the go at the moment,” he says.

A house relocation and renovation in Shepparton was a much more successful venture, netting him profits of $85,000 (split with his JV partner). Michael’s current projects include subdividing a house and land, and building two separate properties in the backyard; creating a multi-room ‘share house’ on another block of land; and a commercial property on top of which he plans to construct studio apartments.

“My belief is that if you can manufacture growth, that’s the way to go. I’ve never been taught to invest just for capital growth,” Michael says.

“My first development experience was really difficult to get through. Not all people have to go through something like that in order to find success, but I do see it as a positive and as a learning curve. And now, I’m looking at playing a bigger game.”

.JPG)