By law, a trust is a relationship under which the trustee of the trust looks after the trust’s assets for the benefit of the beneficiaries.

If it is set up properly, a discretionary trust may offer reasonably effective asset protection as the beneficiaries of the trust are generally not entitled to the income and/or capital of the trust, until the trustee makes a resolution to distribute the income and/or capital.

Therefore, if the investor is sued for whatever reason, but has used a properly established discretionary trust to buy a property, creditors of the beneficiaries do not generally have any recourse against the assets held by the trustee. This is because the beneficiaries do not really own these assets – the trust owns the assets. An exception to this principle is in relation to Family Court matters.

While a unit trust may not be as powerful an asset protection vehicle as a discretionary trust, it may still afford a level of asset protection, depending on how the units in the unit trust are held.

To that end, a unit trust may overcome some of the tax impediments associated with a discretionary trust. Multiple parties from different families can be involved in a unit trust, while retaining the general tax benefits associated with trusts. This is why a unit trust is still a popular choice of structure for property investors.

Passing through depreciation and capital works benefits

Perhaps one of the main reasons for trusts being favoured as a property investment vehicle, instead of a company, is its ability to pass on any net cash profit. These profits can be passed from the property that represents non-cash depreciation and capital works deductions, to the beneficiaries (or unit holders in the case of a unit trust).

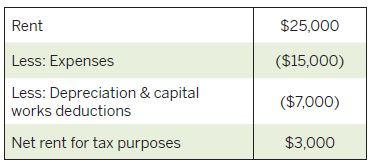

As an example, consider the annual net rent derived on an investment property as follows:

Given that the depreciation and capital works deductions are not ‘real’ cash expenses, the net cash available to the investor from the investment property will be $25,000 – $15,000 = $10,000.

If the investment property is owned by a company, the payment of the net cash profit of $10,000 to its shareholder will usually be treated as a taxable dividend.

However, if the investment property is owned by a discretionary trust, notwithstanding the fact that the trust has distributed the $10,000 in cash to its beneficiaries, the taxable distribution to the beneficiaries will be limited to $3,000, as the trust can essentially pass on the depreciation and capital works deductions to which it is entitled to the beneficiaries.

Given the other benefits associated with a unit trust, it is commonly used where there are multiple property investors from different families

to the beneficiaries will be limited to $3,000, as the trust can essentially pass on the depreciation and capital works deductions to which it is entitled to the beneficiaries.

A unit trust has a similar ability to a discretionary trust in this regard but involves an additional level of complexity. Using the same example above, while the unit holders will only be assessed for tax on $3,000, the $7,000, being what is colloquially known as an ‘E4 amount’, will generally reduce the cost base of the units. As the cumulative E4 amounts distributed by the unit trust exceed the entire cost base of the units, any excess will give rise to

a taxable capital gain in the hands of the unit holders.

It should be noted that the combination of this E4 mechanism and the requirement to reduce the cost base of the property when the unit trust sells the property by the cumulative capital works deductions to which it was entitled (if the property was acquired after 13 May 1997) could potentially give rise to double taxation, but this has been a known issue.

Given the other benefits associated with a unit trust, it is common, where there are multiple property investors from different families, to still use a unit trust to own their properties, despite this double taxation problem.

Passing on 50% CGT discount

Unlike a company, which is not eligible for any capital gains tax (CGT) discount, a trust is eligible for the 50% CGT discount provided that the trust has held the property for at least 12 months before it is sold.

However, if the trust distributes the discounted capital gain to its beneficiaries (or unit holders in the case of a unit trust), the beneficiaries are required to ‘gross up’ the capital gain by multiplying the discounted capital gain by two. Assuming that the relevant beneficiary is an individual, the grossed-up capital gain will first be offset by any capital loss the relevant beneficiary has before the remaining capital gain is subject to the 50% CGT discount in the hands of the beneficiary again.

For a unit trust where the E4 amount would give rise to a taxable capital gain in the hands of the unit holders, it is important to note that the capital gain will also be eligible for the 50% CGT discount, provided that the unit holder has owned the units in the trust for at least 12 months.

Recouping tax losses

Any negative gearing loss generated by a property owned by a trust is usually trapped in the trust, unless the trust has other income to offset the loss. While the trust can theoretically carry forward tax losses for an indefinite period, the losses can only be recouped if certain trust loss recoupment tests are satisfied under the ‘trust loss provisions’.

"Any negative gearing loss ... is usually trapped in the trust"

The same applies to any capital losses incurred by the trust.

For a discretionary trust, the trust loss recoupment tests may be simplified by way of the trust making a ‘Family Trust Election’, but once the election is made, and a trust distribution is made to an outsider who is not part of the family group for which the election is made, the Family Trust Distribution Tax will apply.

For a private closely held unit trust, the trust loss provisions generally allow a unit trust to recoup tax losses if the majority unit holders of the relevant trust continue to own the units of the trust from the start of the loss-making year to the end of the loss recoupment year. However, this test is only relevant if the unit trust is a ‘fixed trust’.

For quite some time, it was assumed that most unit trusts were fixed trusts until a number of relatively recent legal precedents suggested that it was extremely difficult from a technical point of view for any unit trust in Australia to qualify as a fixed trust.

As a consequence of these common law cases, there is now an increasing risk that unit trusts with carried-forward tax losses would not have been or will not be able to recoup tax losses (unless they make a Family Trust Election, which may not be appropriate if the unit holders are not part of the family group).

To that end, there is no need to be alarmed at this point, as the ATO, as an administrative practice, will still treat a unit trust as a fi xed trust (provided that the trust deed includes certain provisions to ensure that dealings in the units of the trust are required to be effected at market value). Nevertheless, watch this space as the technical position of the law will need to be reconciled with commercial practice sooner or later.

Distributing income and capital gains

For taxation purposes, a discretionary trust provides maximum fl exibility in terms of the annual net rental income of the trust and/or any capital gain on the sale of an investment property. This is because the trustee has the discretion to distribute different amounts of income and capital gain to different beneficiaries, having regard to the respective tax position of each beneficiary from year to year.

However, a unit trust will not have the same flexibility as the unit holders are generally entitled to the income and/or capital gain of the trust that is proportionate to their unit holdings. In this regard, unit holders of a unit trust are like shareholders in a company, who are generally entitled to distributions based on their proportionate interest in the entity.

An important point to note about trust distributions is that, under the current tax law, a trust must have resolved to distribute its annual income to its beneficiaries on or before 30 June each year to avoid the trustee being taxed on any undistributed income at the highest marginal tax rate.

Therefore, it is critical for the trustee of a trust to have made a trust distribution resolution to distribute all of the income to beneficiaries on or before 30 June each year.

This is probably less critical for a unit trust as the trust deed of a unit trust would often include a provision that automatically distributes the income and/or capital gain of the trust to the unit holders. In that regard, it may be worthwhile to consider the inclusion of a ‘default beneficiary clause’ in the trust deed of a discretionary trust. This would ensure that the inadvertent failure to distribute the income of a discretionary trust by the end of the year would mean that the default beneficiary or beneficiaries will automatically become presently entitled to the trust income, which would avoid the trustee being taxed on any undistributed income at the highest marginal tax rate.

Conclusion

As illustrated above, while trusts can be useful investment vehicles, the tax issues associated with them can also be highly complex. In this regard, it is advisable to always engage professional advisors whenever trusts are involved to ensure that you do not inadvertently fall foul of any tax rules.