Actively pursuing bargains can have catastrophic consequences if you’re not aware of the pitfalls. I actually recommend investors avoid buying under market value. Sounds crazy? Hear me out.

Defining terms

Before going any further there’s some bargain jargon we need to clarify:

• Buying at a discount

• Buying a bargain

• Buying under market value

Buying at a discount

Buying at a discount is buying a property for less than the original asking price. This is nothing special; it happens a lot. The discount is the difference between the original asking price and the eventual sale price.

Real estate agents routinely add an extra amount to the expected sale price. This is so buyers like us can feel better about ourselves after successfully haggling the seller down to the price they were going to sell at anyway.

It is possible to buy a property at a heavy discount and still pay too much for it. The discount may simply not have been enough.

Many investors actively pursue heavily discounted properties. There are more success ‘stories’ with this strategy than there are legitimate successes. The reason why is that the strategy has some serious issues that make it either quite tricky to pull off; or not as profitable as first thought; or downright disastrous – more on that later.

Buying a bargain

It is possible to pay more than the asking price and still get a bargain. For example, the seller may not know the potential a property really has.

A bargain is really quite subjective. It all comes down to opinion. One buyer’s bargain is another buyer’s barn.

Buying under market value

Buying a property under market value is buying a property for a price that is less than the recent market valuation that a professional valuer has placed on the property. This is the strategy most investors want to succeed at.

Before a property has been sold, we actually don’t know its market value; we can only estimate it. But on the day it sells, the market value is precisely the price it sold for. So, technically, it is impossible to buy under market value. What we mean when we say ‘under market value’ is that the sale price is less than what the property should have sold for in someone’s opinion.

And there’s the crux of it – whose opinion counts?

How to determine market value

The usual method for determining market value is to find the sale price of similar properties that have sold recently in the same area. Your lender’s valuer will do exactly this, but they may interpret the data differently to you and will probably be more conservative in their figure.

There are more success ‘stories’ with this strategy than there are legitimate successes

So, who has the final say on valuation? How can you determine the true value of a property?

If you’re looking to buy a bargain, your opinion is the only one that matters. But the investor looking to profit from buying properties under market value should put their own opinion aside.

There are only two opinions that count: the opinion of your lender’s valuer and the opinion of the next buyer.

Let me just back up a bit. There are two ways to cash in on the equity you have acquired in a property: you can either borrow against that equity or you can sell the property.

To borrow against a property’s equity you need a lender. And to sell a property, you need a buyer.

How much you can borrow comes down to the opinion of the lender on the value of the property. And how much you can sell for comes down to the next buyer’s opinion about the value of your property. The next buyer’s opinion will be very heavily influenced by the valuation their bank comes to.

So the true market value is looking more and more like the opinion of a bank’s valuer. That’s either your own bank’s valuer or the seller’s bank’s valuer.

You can get an idea of value by asking your own lender. But keep in mind that valuations can differ from one valuer to another.

Once you’ve got a good idea of value, the profitability of buying under market value comes down to the difference between the valuation and the agreed sale price.

Note that many valuers will request the contract price prior to performing their research as a gauge for them to determine the value. If the value they initially come to is above the contract price, they will slide that value down to the contract price to err on the side of caution.

Distressed developers

Developers have a tendency to focus on demand and ignore supply. They often build in a location with loads of infrastructure projects mentioned in the news, without considering whether there are already enough properties available for sale.

Oversupply creates desperate sellers. But a drop in demand can also create a similar scenario.

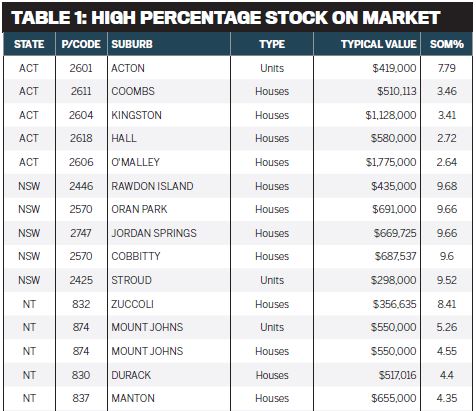

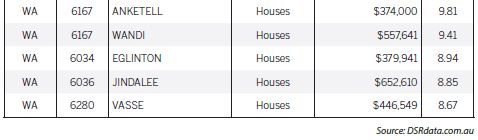

Looking for locations with a large percentage of stock on market (SOM%) will uncover these problem areas. Table 1 provides a list of some of the higher SOM% figures from around the country as at the end of March 2016.

What’s a good SOM%?

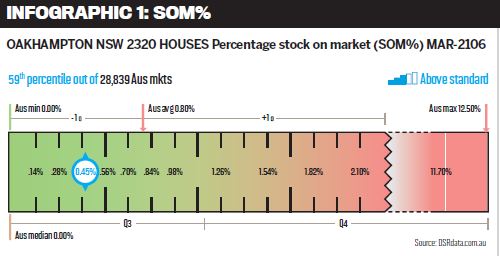

Most investors know what a good vacancy rate is, but do you know what a good SOM% is? Infographic 1 is called a context ruler because it places a statistic in context by comparing its value to other values for the same statistic in other markets around the country.

Infographic 1 shows that Oakhampton houses had an SOM% of 0.45% for March 2016. The blue oval marker appears on the left side of the context ruler, which is green. Green means good; red is bad.

An SOM% of 0.45% is a better-thanaverage SOM%. The average SOM% Australia-wide was 0.8%. You can see that above the context ruler near the brown down arrow.

Any figure for the SOM% up to about 1.25% is nothing to worry about. But figures over 2.5% should trigger alarm bells. To make that obvious, they appear in the red section to the right of the ruler.

If you don’t have access to this data for your target suburb, you can roughly gauge oversupply by simply driving down several streets in the suburb you’re researching. Start counting houses along a street while looking for any ‘for sale’ signs. If you can’t count 40 houses in a row before seeing a ‘for sale’ sign, then that market probably has an oversupply issue.

Gotchas

As a general rule I avoid heavily discounted or under-market-value properties. While not meaning to put you off the strategy, I’ll just give you a ‘heads up’ on some of the issues so you’re better prepared.

Personally, I have an ethical problem with buying under market value, knowing the seller is distressed. I don’t feel comfortable kicking someone in the teeth when they’re already on their knees. I don’t like to badger another dollar out of someone else’s pocket simply to line mine with it.

In most cases the genuine ‘under market value’ opportunity comes from a distressed seller.

What’s a ‘distressed seller’?

An owner who has run into financial difficulty:

• Eg a developer whose project went pear-shaped due to unexpected costs or delays

• Or perhaps a homeowner who lost their job

A seller who doesn’t care what price the property sells for (within reason):

• In the case of a deceased estate the next of kin just wants to get rid of the property, so arguing over a few thousand extra may seem petty

• In a divorce settlement emotions like spite may cloud judgment or there may be bigger issues at play like kids, so the property price becomes a casualty instead

• In the case of bank repossession, the lender simply wants their $400k loan back (plus costs), so selling a $500k property for $450k will be fine, thanks

An owner on a tight deadline, eg selling their current home before settling on their new one. may have to agree to a lower price for a quicker settlement

Finding such opportunities isn’t easy. These are the common approaches:

1. Scan properties for sale, analysing the description to see if the selling agent has mentioned a distressed seller

Note that if the agent does this, they’re effectively shooting their client’s chance of getting a fair price in the foot.

2. Build relationships with selling agents in your areas of interest so they contact you before going to market

Note that agents will get frustrated with you continually turning your nose up at the properties they currently have on the market. And they may have a list of other buyers like you waiting for a distressed seller.

3. Hire a buyer’s agent who either already has relationships with agents or is prepared to build them just for you

A buyer’s agent won’t do this for free.

There is a way to increase your chances of finding such opportunities, but I really wouldn’t recommend it. You can target markets in which there are higher proportions of distressed sales. There are some indicators that can point to such markets, which I’ll explain in this article.

Some would argue that if the vendor signs a contract, they are ‘agreeable’, so what’s all the fuss about? You may even be helping them out of a tight spot. And some will consider mercy ill-placed if the vendor is a developer anyway – they are the enemy, right?

Whatever helps you sleep at night. Everyone is different; I’m not judging.

If it does make you a bit squirmish but you want to pursue a distressed sale, you can always employ the services of a buyer’s agent to palm off these awkward jobs.

But how do you know the vendor is actually distressed anyway? Did they provide you with their balance sheet, or was it just a marketing ploy by the real estate agent?

What’s worse than kicking a distressed vendor in the teeth is discovering they were actually licking their lips right from your first foot-inyour-mouth offer. Ah, the bargain hunter has become the hunted.

A question you should ask yourself is why you were able to snap up this bargain and not someone else. If you didn’t have your finger on the pulse of the market or you weren’t quick to make an offer, how come you got it for below market value rather than someone else? Is nobody else looking?

If nobody else is looking at the market you’re targeting, then you need to question demand for property in this market. The markets with the strongest demand-to-supply ratio will have the highest number of people looking for the lowest number of properties available.

It should be difficult for an investor to get any property in a good market, let alone one for a steal. A good market to buy in will have demand comfortably outstripping supply. Every buyer will need to act quickly, even if just to pay full market price.

Inexperienced investors will find recognising a genuine opportunity difficult and the timing challenging. Obviously, if an excellent deal does come on to the market, you’ll need to identify it straight away and move fast and with confidence.

The discount flip

You’ve probably heard of the ‘reno flip’ – buy a property, renovate it and then sell it, all in a short space of time. But I’ll bet you haven’t heard of the ‘discount flip’ investment strategy. That’s because there isn’t one.

It is extremely difficult to buy a property under market value and then sell it straight away for market value or more.

Once you’ve bought at below market value, the new market value of the property you just purchased is the purchase price you just paid. The next buyer will see a record of the sale and will know the real value of the property. So will their valuer.

You could try to onsell before the information about your sale appears in various databases that are available to the buyer and valuer. But your timing has to be spot on.

And who is going to pay full market value at a time when the market is soft enough for you to buy it for under market value? Where was that generous buyer only a few weeks ago?

OK, so what about a top-up then instead of selling? Will this work? Can you simply refinance to obtain the so-called instant equity? No, you can’t.

There is no way you can approach your lender straight after settlement and ask for a top-up based on the new equity you think you have. The new valuation will be the price you just paid. Valuations are based on recent sales of similar properties in the same location.

The lender will have undeniable evidence to support their claim that the value hasn’t changed since you bought it. They’ll say, “A property exactly the same as yours, in the

There’s no such thing as a discount flip strategy. What you just paid for the property is its new value. There is no instant equity.

Many lenders won’t consider a revaluation until at least six months have passed. If the market hasn’t dropped in that time, then you may be able to cash in on your strategy.

And why would the market drop, I hear you ask? Well, for starters your cheap purchase will guide the price of the next sale. Seeing a low sale will discourage other buyers from paying more than you did. Your cheap purchase may become the new benchmark.

This could potentially drag down the values. If there are enough sales of the same value, you can give up on getting a higher value from your lender six months down the track.

Supply and demand is against you

The stronger the market, the less likely you’ll find a distressed seller. In a hot market, demand exceeds supply. Sellers have no problem selling so they don’t get distressed. However, sellers do get distressed when they really need to sell but the market is so weak they can’t.

There’s no such thing as a distressed seller in a hot market.

In a bad market, however, every seller is distressed. Sellers won’t get a good price and will have to wait unless they drop their asking price significantly.

In an average market there will be some distressed sellers but not in alarming numbers.

Can you see a relationship now between bad markets and distressed opportunities? They go hand in glove.

Distressed sales are generally an indicator of a bad market to buy in, especially in thinly traded markets. It may only take one low sale to put doubt in the minds of buyers

A good market is one in which there are no distressed sellers. That’s why you should actually avoid buying under market value. You should try to find markets where nobody has been able to buy under market value.

Big-discount bonanzas

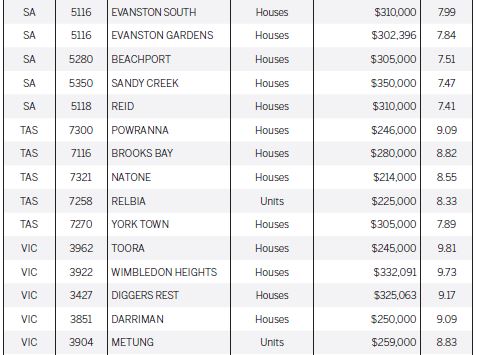

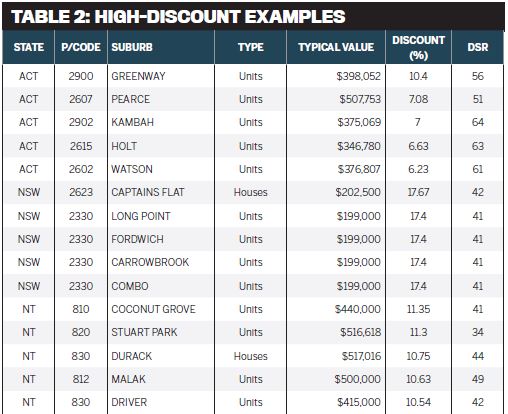

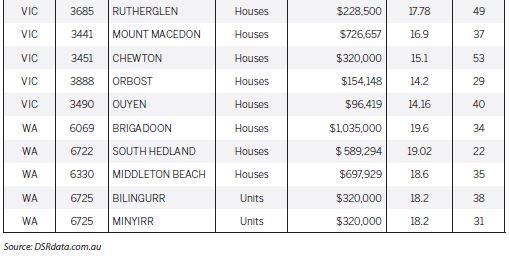

The greatest discounts and the greatest number of distressed sellers are in the worst locations for capital growth. But if you’re hell-bent on this strategy, see Table 2 (p50) for a list of Australia’s highest-discounted markets as at the end of March 2016.

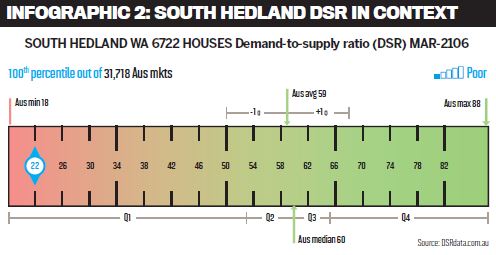

The typical discount for houses selling in South Hedland (a mining town in WA) is around 20%. Infographic 2 places the DSR for South Hedland houses in the context of the rest of the country.

As you can see, this is a pretty bad market to invest in. Either demand is very weak or supply is very high or both!

The data shows the correlation between markets with low DSRs (ie weak markets), and high discounting. So why would an investor want to pursue such ‘opportunities’?

Discount distractions

Trying to buy under market value can distract investors from more important and lucrative opportunities such as capital growth, renovation or development potential.

If your sole strategy is to buy under market value, then once you’ve bought, you’ve locked in your profit. The clever part of your plan has ended for the rest of your ownership of that property.

I prefer to focus my attention on finding the best locations to buy in and then paying fair market price to secure a great property

So now what? Sell it?

Unless there is something else going for the property, like capital growth potential or renovation potential, there could be little further profit to be made. That 10% discount will seem pretty inconsequential after you’ve been holding a stagnant property for three years of zero growth.

Entry and exit costs

Another problem is that finding a true property under market value by a significant amount can be difficult. By ‘significant’ I mean enough to buy, sell, pay tax and make a profit. Remember there are entry and exit costs such as:

• stamp duty

• legal fees to purchase

• building and pest inspections or strata reports

• sales agent’s commission when selling

• more legal fees on the sale

• capital gains tax (CGT)

And this is not to mention the cost of your own time to make this churn happen.

Unless you’re buying for around 20% or more below true market value, you’ll find it hard to buy and sell and make a worthwhile profit after tax for your effort.

Remember that if you sell within 12 months you won’t get the 50% CGT discount. At best you could buy in a company name and pay 30% of your profits to the ATO. But if you’re a salary earner and the company has no additional income, then you will have no income against which to claim negative gearing.

There’s a reason there is no such thing as a ‘discount flip’.

If the plan is to buy and hold rather than sell, then you’re better off thoroughly researching a growth market and paying fair market value than looking for a so-called bargain in an ordinary market. Remember, there’s no such thing as a distressed seller in a good market.

Success stories

I’ve seen a lot of examples of investors claiming to buy under market value by monstrous amounts. But almost every time I analyse the details, there is some other factor that played a bigger part in the impressive profit.

I’m amazed at how many of these examples involve a renovation or a long delay before revaluing or selling. Take off the capital growth for that delay or the value-add for the reno and the true amount by which the investor bought under market value is not at all impressive for most examples.

That’s not to say such deals never happen. I’m sure they do. But they are less frequent than most investors realise and not nearly as impressive as the tagline that catches our eye.

For every investor who claims a success in buying under market value, I’m sure there are a dozen more we never hear about who can tell you about a failure. No one who is a proponent of this strategy will tell you about all those failure stories.

This is not an easy strategy to get right given that it has so much going against it.

Counter-intelligence

I prefer to focus my attention on finding the best locations to buy in and then paying fair market price to secure a great property. I’d even pay above market value if it meant getting into the best market.

Some would argue it’s insane to pay more than market value. But the only way capital growth can occur is when the majority of buyers are paying above market value. If the majority of buyers are paying less than market value, you’ve found a falling market.

Call it counter-intelligence, but I’d rather enter a market on the rise than one in freefall. So for me it is insane to buy into a market where bargains are possible.

I’m not saying you can’t make a profit from buying ‘under market value’. I’m not saying genuine deals don’t exist. I’m just presenting my reasons for disliking the strategy in principle. It can really set you up for failure if it becomes your primary focus and you actively hunt out distressed markets.

I would rather pay top dollar to secure a property with loads of potential than scrounge around in an ordinary market looking for a seller who has all but given up trying to offload their problem.