In November, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) revised down its growth forecast for 2019 to 2.25% – well down from the 3.25% forecast one year ago. This downgrade is in line with the average downgrade seen to its growth forecasts since 2012.

While it predicts growth of 2.75% in 2020, the risk is that yet again this may be too optimistic. There is not much sign of the “gentle turning point’’ in consumer spending that RBA governor Philip Lowe has spoken of, with real retail sales falling in the September quarter and vehicle registrations down again in October.

The RBA sees little progress in getting unemployment down before 2021, with wages growth stuck at 2.3% for the next two years. This is to say nothing of the 8.5% of the workforce that’s underemployed.

After revising down its inflation forecasts again, it sees inflation remaining below target for the next two years. After nearly five years already of below-target infl ation, the inflation target is losing credibility. In fact, the RBA says “it is possible that wage expectations have become anchored at low levels as a result of a prolonged period of low wage and inflation outcomes”.

My view is that the RBA is likely to ease monetary policy further in order to get to “full employment and the achievement of the inflation target over time”.

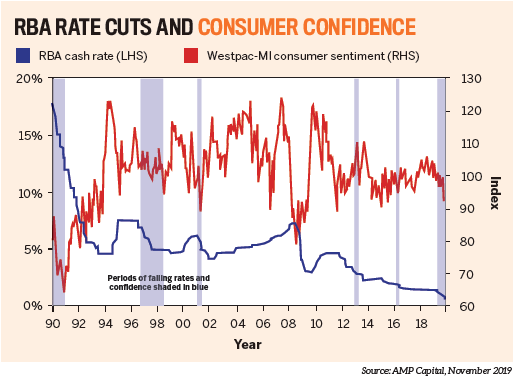

History shows that it’s quite normal for consumer confidence to fall during the initial phase of a rate-cutting cycle. This is because both are reacting to the same bad news on the economy, and because monetary easing only boosts growth after a lag. So the current decline in rates and confidence is not unusual.

While I don’t buy the argument that rate cuts are making things worse, the case for more fi scal stimulus is getting louder and louder. This should involve a mix of measures, such as bringing forward some of the stage two tax cuts, boosting Newstart, inducements to large companies to invest more, and increased infrastructure spending. Fiscal stimulus would give a far more assured boost to the economy and could be more fairly targeted than the blunt instrument of monetary easing.

Drought assistance will help, but it’s too small at less than 0.1% of GDP to have much impact on the economy. Finance Minister Mathias Cormann has implied an openness to bringing forward tax cuts, but this may still be a long way off.

In the absence of significant fiscal stimulus soon, pressure remains on the RBA for further interest rate cuts if it is to achieve its mandate. However, with bank interest margins under pressure, this should come with quantitative easing measures designed to lower bank funding costs and increase the banks’ pass-through of rate cuts to borrowers. The RBA’s forward guidance is also likely to be toughened to, say, something along the lines that the RBA “doesn’t expect to consider raising interest rates until inflation is near the mid-point of the 2–3% inflation target”.

Shane Oliver

is AMP Capital’s head of investment strategy and chief economist