Without sounding too simplistic, there’s a grain of truth to feeling nostalgic about ‘the good old days’ when it comes to urban planning and our residential communities. Over hundreds of years, we seemed to get the urban mix right, only to turn it on its head in the last 20–30 years – before realising we had it right the first time.

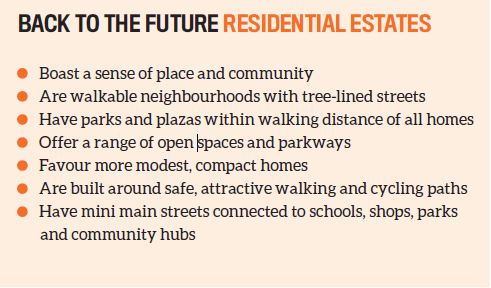

Big houses on even bigger blocks in residential-only enclaves are losing popularity in favour of more integrated communities with a sense of place and belonging.

Planners were previously obsessed with separating land uses to minimise conflicts between uses. Housing was in one part of the suburb, with shopping centres and business parks only accessible by car, resulting in segregated communities, with people forced to drive everywhere. As most contemporary land uses are compatible, we are now planning for them to coexist.

Streets became primarily designed for cars and not for people. Enormous homes taking the entire footprint of massive blocks meant people kept to themselves and internalised life, rather than meeting at community hubs.

Now, people are seeking a return to good old-fashioned community life, with connected footpaths leading to neighbourhood squares or urban plazas (places to congregate), with schools, shops, restaurants, cafes and community facilities within walking distance. We don’t want to drive so much, and exercise is becoming more popular.

We have seen more urban places developed outside inner-city neighbourhoods in the last few years, and with new ways of moving around, such as e-bikes, e-scooters and trackless trams, the concept will become even more popular. In other words, we are urbanising the ’burbs.

Transit-based, compactconnected, walkable, mixed-use neighbourhoods are back in style. The most progressive contemporary urban neighbourhoods of the future will contain a diverse range of housing types, with more modest, smaller and affordable homes framed around local mixed-use community hubs, including green spaces, amenities, shopping and health facilities.

With the increasing cost of owning a car and the negative environmental impact, many young people are deferring or not getting their driver’s licence and are, in turn, seeking out connected communities near transport hubs if they need to commute to work, and within easy walking or cycling distance of all their daily needs.

In Europe, urban centres are increasingly becoming car-free zones, and there’s no reason the model can’t exist in Australia. Already many younger people are choosing where to live using Walk Score, an app increasingly used in the USA and Australia that ranks the ease of walkability from your home to schools, shops, parks, jobs and transit, with a score out of 100. A Walk Score of 70 is the threshold for not having to own a car, which can save you more than $10,000 a year – and service almost $100,000 of a mortgage.

Housing estates are moving ‘back to the future’, like Marty McFly’s Hill Valley of the 1950s and 2015. If you want to invest in the estate of the future, focus on community, convenience and accessibility. And until hoverboards become a reality, we can use electric bikes.

Mike Day is co-founder and director of urban development consultancy RobertsDay, a fellow of the Planning Institute of Australia and a recipient of the Russell Taylor Award for Design Excellence